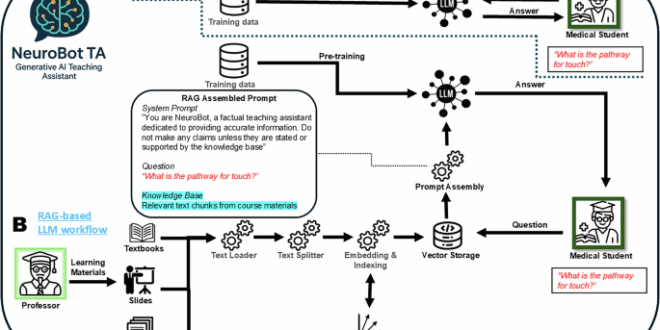

This study examined the implementation of a RAG-based AI teaching assistant in medical education across two consecutive academic cohorts and demonstrates a scalable, always-available AI support tailored to curricular contexts and students needs. The results identified both opportunities and challenges in deploying RAG-based AI teaching assistants in medical education programs.

The data from participating students demonstrate how some medical students integrated NeuroBot TA into their self-regulated learning processes. Students exhibited strategic, context-dependent usage patterns rather than continuous engagement. The 329% surge in usage during pre-exam periods and substantial after-hours utilization (post-5 pm) indicate that students primarily leveraged the system as a just-in-time learning resource during intensive study sessions that often extended beyond the hours of instructor availability. The average conversation length of 3.6 turns suggests focused, targeted queries rather than extended tutoring sessions. This pattern indicates that medical students use the chatbot as a targeted reference tool during self-directed study, asking specific questions to clarify concepts rather than seeking extended tutoring or comprehensive instruction.

The RAG-based design showed mixed results in enhancing perceived usefulness through increased trust. Positive indicators included students’ appreciation for source citations (26.3% of feedback comments mentioned trust and reliability themes), with one student noting that knowing “the NeuroBot TA only pulls from class materials” increased confidence. The predominance of curriculum-aligned queries (66% neuroanatomy, 54% clinical disorders) suggests students trusted the system for course-specific content. However, the modest usefulness ratings (2.8/5 and 3.3/5 across cohorts) and the “limited scope” frustration theme (36.8% of comments) indicate that while restricting responses to content in the course materials may enhanced accuracy and trust, it simultaneously reduced perceived utility of the tool by restricting response breadth, thereby creating a tension between response reliability and comprehensiveness.

The conversational interface and 24/7 availability did improve perceived ease of use, as evidenced by usage patterns and feedback. Some users valued the “convenience and integration” (26.3% of feedback), with comments highlighting quick access to answers during exam preparation. The temporal distribution showing after-hours usage and mid-week engagement peaks suggest that users found the system accessible when needed. However, some students noted challenges with prompt engineering (10.5% mentioned prompt sensitivity), suggesting that while the interface was accessible, optimal utilization may have required AI skills students were still developing.

These findings collectively support our TAM-based hypothesis partially: students adopted NeuroBot TA when perceived benefits were most salient (pre-exam periods), but overall adoption remained moderate (31.4%) due to the tension between the system’s reliability constraints and students’ expectations for comprehensive support.

Content analysis of the chat transcripts confirmed that students primarily used NeuroBot TA to reinforce core course knowledge. The vast majority of queries centered on the course’s fundamental content and neuroanatomy and neurophysiology concepts were the single largest topic, appearing in about 66% of conversations, and clinical neurological disorders appeared in ~54%. Students also frequently asked about study resources or clarifications of course logistics (appearing in roughly 28–31% of chats, e.g., exam information or “high-yield” review tips). Other academic topics like neural pathways, tract anatomy, and pharmacology were moderately represented, whereas more complex clinical case discussions or neuroimaging interpretation were relatively infrequent. This distribution suggests that the AI assistant was mostly used for fact-based clarification and review of taught material, rather than for open-ended clinical reasoning practice. It may also reflect the constraints of its knowledgebase as NeuroBot TA was intentionally limited to instructor-curated course materials, which ensured answers stayed aligned with the curriculum but inherently capped the scope of questions it could address. The content pattern therefore illustrates a trade-off where the bot excelled at fielding questions on covered topics, but students may have recognized that queries outside the provided content, or requiring extensive synthesis, were beyond its scope.

Student feedback on NeuroBot TA highlighted both the promise of AI support as well as opportunities for improvement. Qualitative comments showed that while many appreciated the bot as a convenient supplemental resource, its performance was inconsistently helpful. The most prevalent theme in feedback was “variable helpfulness” and students noted the AI could answer certain questions well (for example, providing quick explanations or grading clarifications) but failed at other tasks (such as generating comprehensive study guides). Similarly, nearly half of commenting students viewed NeuroBot as a “supplementary learning aid”, valuing the ability to get instant answers during self-study (e.g., while preparing for exams). On the other hand, many users were frustrated by the system’s “limited scope” and about 37% of comments noted that the bot could not address numerous questions, especially those requiring information beyond the uploaded course slides. This limitation sometimes led students to revert to other AI tools or resources for comparison. Additional feedback themes underscored practical considerations. For example, some praised the convenience and integration of the 24/7 chat format within the learning platform, noting it saved time searching through slides. However, trust and reliability emerged as a concern (26% of comments) where a subset of students expressed reluctance to fully trust any AI-generated answers without verification. Encouragingly, students acknowledged that constraining the bot to official class materials through RAG improved their trust. Lastly, some users mentioned that the quality of answers depended on how questions were asked, with the bot sometimes giving overly lengthy answers to simple questions. This indicates that students were still learning how to interact optimally with LLM chatbots, which is an expected challenge as both users and technology co-evolve.

Usage declined notably in cohort 2, potentially reflecting the rapidly evolving GenAI landscape. When deployed with cohort 1 in Fall 2023, NeuroBot TA represented novel technology less than 10 months after ChatGPT’s initial release. Internal survey data indicated limited prior AI experience among cohort 1 students, making the Neurobot TA system novel and distinctive. Conversely, cohort 2 in Fall 2024 entered during a period of more widespread AI adoption in higher education. Medical student utilization of general AI platforms increased dramatically during this period, with up to 89% reporting regular use24. While the present study design does not allow us to draw clear inferences, the growing availability of commercial alternative models with reasoning capabilities that are demonstrating improved performance on medical knowledge benchmarks may lead students to use these systems more frequently25,26. The usage patterns observed with NeuroBot TA seem to reflect this demand for quick, accessible support where students tended to use the assistant as a just-in-time tutor during intensive study periods (notably mid-week and pre-exam) when instant clarification of concepts was most valued.

The finding that conversation volume increased substantially during pre-exam periods demonstrates how assessment events can drive the use of self-directed learning resources, including AI chatbots. This behavior indicates that students viewed the system primarily as an optional review tool rather than a continuous learning partner and suggests a strategic but yet limited integration into their study practices. The course where the chatbot was deployed was the last organ-system course at the end of Year 2 in the preclerkship curriculum. At this point students will have already found their preferred study method and tools and are therefore less likely to engage in strong shifts in how they study and take the risk of adapting a new, untested study tool. This may have affected the moderate adoption rate despite the societal hype of Generative AI at the time. In the future, implementation of RAG-based AI tutor system may early in the medical school curriculum when students have not yet solidified their study approach may lead to higher adoption rates, and should include best prompting techniques for interacting effectively with AI-teaching assistants.

There was a clear hierarchy of student learning priorities through chatbot interactions, with core biomedical content dominating conversation frequency, followed by clinical disorders, a finding that matches the content and focus of the preclerkship course. Students also asked a significant number of questions about course organization and exams, highlighting the utility of RAG-supported LLMs in answering questions specific to an individual course based on information that was not part of the original LLM training data. To that end, students primarily leveraged the AI assistant for clarifying course content and reviewing concepts, treating it as an on-demand tutor for course-related content.

Overall, students demonstrated moderate willingness to engage with the course-constrained AI tool, and those who did valued its instant and around-the-clock access to verified information. This availability complements the contemporary nature of how medical students study, as they often study at odd hours, already use digital resources like question banks and online tools, and value self-paced studying. NeuroBot TA provided an additional tool that fit naturally into these eclectic patterns as it was accessible on the same devices they already use and at any time in any location. Additionally, NeuroBot TA’s retrieval-based design provides highly targeted, on-demand explanations that align with students’ individual study goals (e.g., lecture-specific clarification before exams). Overall, the principles of personalization that LLM-based RAG chatbots offer are consistent with the emerging framework of Precision Medical Education that advocates for tailoring educational interventions to each learner’s specific needs and context27,28.

Our findings also align with TAM predictions and demonstrate how perceived usefulness and ease of use shaped NeuroBot TA adoption. The increase in usage during pre-exam periods reflects TAM’s principle that perceived usefulness drives adoption when benefits are most salient. Neuroanatomy-focused conversations and positive responses to source citations demonstrate that curriculum alignment and verifiability enhanced perceived usefulness. Substantial after-hours utilization suggests that students found the system accessible when most convenient, satisfying TAM’s ease of use dimension. Finally, frustration regarding knowledge scope limitations highlights TAM’s expectation alignment principle. This principle predicts that when system capabilities do not match student expectations, student satisfaction decreases, underscoring the importance of clearly communicating system capabilities and boundaries in educational AI implementations.

Notably, NeuroBot TA’s intentional constraint to its knowledge base led to student frustration when it refused to address queries beyond the scope of the knowledge base. This compares directly to all-purpose commercial chatbots who typically provide plausible-sounding answers regardless of factual accuracy. Student comments help illustrate this point in the context of the evolving GenAI landscape and the frustration with restricted answer space. A cohort 1 student, for example, noted, “The chatbot is interesting to play around with but if I have a question, I tend to just pull up Google because it is convenient and is what I have done my whole life,”, highlighting the student’s unfamiliarity with Generative AI chatbots and preference towards established strategies to access knowledge. In contrast, a cohort 2 student stated, “ I use other AI tools to help create comparative/summary tabels (sic) and this was very helpful, but Neurobot ta wasn’t able to answer a lot of questions.” A year later, the cohort 2 student had already incorporated GenAI technologies into their study practices, but valued unconstrained answers even if the likelihood of factual incorrectness may be higher.

Pedagogically, educators can address this through explicit instructions in Generative AI uses and misuses and providing students with the knowledge how to responsibly navigate these new and ubiquitous tools for their learning. Technically, future work may focus on developing RAG-based systems that are able to generate flexible study schemes that matches a student’s learning habits (e.g., automatic generation of lecture-specific tables or flash cards) and showing students how to most effectively initiate conversations with specific aims.

With only a subsection of students using NeuroBot TA and survey responses from a subset of students who reported usage, our findings do not represent the entire medical student population. Statements about student preferences and strategic adoption should be interpreted within this self-selected sample in mind. In addition, the per-conversation analysis could not distinguish whether usage patterns reflected typical behavior or were driven by a small number of “super users,” as we did not track individual user engagement. This limits the ability to generalize directly to the average student experience. Despite theoretical and empirical works demonstrating reduced hallucinations and increased relevance of RAG-constrained responses, the current study did not systematically assess response accuracy. While periodic informal review by the course director identified no critical issues requiring intervention, we cannot quantify accuracy improvements or definitively confirm that RAG constraints eliminated all hallucinations. Finally, the content analysis relied primarily on GPT-4o for thematic coding with human validation of only 15% of conversations for theme coherence rather than comprehensive accuracy assessment. This approach, while efficient, may have missed errors that the LLM could not identify. Lastly, the deployment of the tool at only a single medical school and restricts the study’s generalizability across diverse institutional contexts with varying curricula, teaching methodologies, and student demographics.

RAG-constrained LLM chatbots show potential as adjunct study tools for some medical students in self-directed learning contexts. However, they need to be deployed thoughtfully in order to engage students meaningfully and contribute to their learning. We recommend that educators introduce the new technology early in the medical school curriculum, preferably in the first course when students are trying different study techniques that work for them in medical school. Educators who are considering broader implementation should focus foremost on carefully curated content that is submitted to the vector database to improve response relevance. Specific documents that contain useful information about the course resources, assessments and effective study strategies should be included to allow the bot to answer questions in this area, as we found that students asked these questions frequently. Bot responses should also enable a deeper dive into the material by highlighting the text sources that were retrieved and to link directly to the document of origin and the place of quotation. Furthermore, educators need to decide whether to restrict the bot to answer questions solely based on course material at the risk of student frustration or to allow increasingly sophisticated models to answer questions beyond immediate course content. Educators also need to communicate system capabilities and limitations clearly to help students select and leverage these tools effectively in their courses. Lastly, medical programs should ensure students gain fundamental knowledge of GenAI, including prompt engineering, to effectively select and use suitable AI learning tools, whether they are provided by the school or through commercial sources.

Several approaches could address the tension between response accuracy and comprehensiveness identified in this study, while also following best pedagogical practices for long-term learning. For example, a hybrid system could clearly mark responses derived from the course-specific RAG database as highly reliable while flagging answers requiring external knowledge with accuracy warnings, which would allow students to assess information trustworthiness. Beyond RAG, knowledge graph architectures could enable more sophisticated cross-topic synthesis while maintaining accuracy through formal ontological constraints that explicitly map relationships between medical concepts29. Furthermore, incorporating Socratic tutoring methods, where the AI guides students through problems with targeted questions rather than direct answers, could transform the system from a passive answer service into an active learning partner that promotes deeper understanding and long-term retention30. Such systems could also adapt their approach based on context, providing direct answers during time-sensitive exam preparation while employing Socratic dialog during regular study sessions to develop critical thinking skills.

Deep Insight Think Deeper. See Clearer

Deep Insight Think Deeper. See Clearer